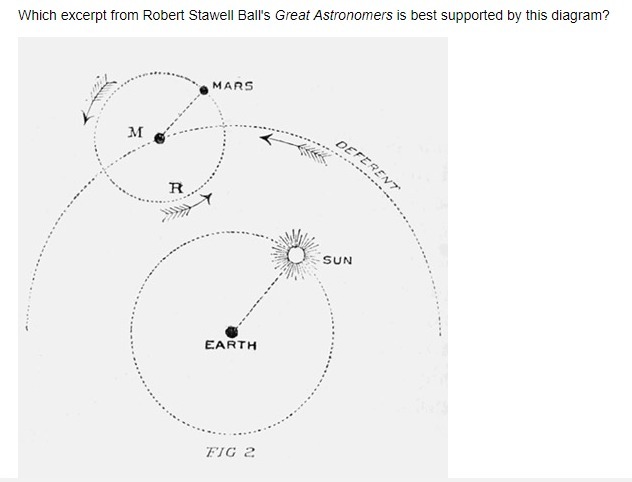

lly incompatible with the supposition that the journeys of Venus were described by a single motion of the kind regarded as perfect. It was obvious that the movement was connected in some strange manner with the revolution of the sun, and here was the ingenious method by which Ptolemy sought to render account of it. Imagine a fixed arm to extend from the earth to the sun, as shown in the accompanying figure, then this arm will move round uniformly, in consequence of the sun's movement. At a point P on this arm let a small circle be described. Venus is supposed to revolve uniformly in this small circle, while the circle itself is carried round continuously by the movement of the sun. In this way it was possible to account for the chief peculiarities in the movement of Venus. Excerpt 2 To understand his reasoning, let us first set forth clearly those facts of observation which require to be explained. I shall take, in particular, two planets, Venus and Mars, as these illustrate, in the most striking manner, the peculiarities of the inner and the outer planets respectively. The simplest observations would show that Venus did not move round the heavens in the same fashion as the sun or the moon. Look at the evening star when brightest, as it appears in the west after sunset. Instead of moving towards the east among the stars, like the sun or the moon, we find, week after week, that Venus is drawing in towards the sun, until it is lost in the sunbeams. Then the planet emerges on the other side, not to be seen as an evening star, but as a morning star. In fact, it was plain that in some ways Venus accompanied the sun in its annual movement. Now it is found advancing in front of the sun to a certain limited distance, and now it is lagging to an equal extent behind the sun. Excerpt 3 It will be seen that, in consequence of the revolution around P, the spectator on the earth will sometimes see Venus on one side of the sun, and sometimes on the other side, so that the planet always remains in the sun's vicinity. By properly proportioning the movements, this little contrivance simulated the transitions from the morning star to the evening star. Thus the changes of Venus could be accounted for by a Combination of the "perfect" movement of P in the circle which it described uniformly round the earth, combined with the "perfect" motion of Venus in the circle which it described uniformly around the moving centre. Excerpt 4 The explanation of the movement of an outer planet like Mars could also be deduced from the joint effect of two perfect motions. The changes through which Mars goes are, however, so different from the movements of Venus that quite a different disposition of the circles is necessary. For consider the facts which characterise the movements of an outer planet such as Mars. In the first place, Mars accomplishes an entire circuit of the heaven. In this respect, no doubt, it may be said to resemble the sun or the moon. A little attention will, however, show that there are extraordinary irregularities in the movement of the planet. Generally speaking, it speeds its way from west to east among the stars, but sometimes the attentive observer will note that the speed with which the planet advances is slackening, and then it will seem to become stationary. Some days later the direction of the planet's movement will be reversed, and it will be found moving from the east towards the west.